Well, have a

- not much competent pilot flying a

- not much competent primary release, a

- not much competent secondary bridle, and a

- not much competent secondary release.

It's a no brainer that he also has a

- not much competent weak link.

Therefore we know that he was trained and signed off by a

- not much competent instructor working at a

- not much competent school

and being towed at a

- not much competent aerotow operation by a

- not much competent tug driver.

The school is Kitty Hawk Kites at which I learned in 1980 and taught and towed (a little) in 1980 and 1982. The people under whom I directly worked were all

- not much competent douchebags

with the exception of Doug Rice:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ls2QiDtSO7c

Rescue 911-Episode 415 "Hanging Hang Glider (Part 1)"

BeatleMoe - 2008/05/14

dead

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZX_6UZ2UWEE

Rescue 911-Episode 415 "Hanging Hang Glider (Part 2)"

BeatleMoe - 2008/05/14

dead

who knew and could communicate his stuff pretty well ('cept - obviously - for the hook-in check issue) but was even more of a social retard than I am.

That tow site is Currituck County Airport and is the facility Kitty Hawk Kites uses for its string based operations. I first platform towed there in 1990 and first towed behind the Dragonfly 1991/08/02-04 during the promotion tour for the new tug. There was room for improvement but aerotowing was never safer. That was one of the coolest, funnest, happiest experiences of my flying career. Kinda glad I didn't know then what I know now.

Kitty Hawk Kites is authorized to operate in compliance with regulations established by the United States Hang and Paragliding Gliding Association so we know that we have a

- not much competent national organization.

The national organization is authorized to aerotow by the Federal Aviation Administration under the agreed upon regulations so we know we have a

- not much competent US public safety agency.

Kitty Hawk Kites is an Authorized Wills Wing Hang Glider Dealer and the primary responsibility of an Authorized Wills Wing Hang Glider Dealer is

A) Offering competent, safe instruction in the proper and safe use of hang gliding equipment.

so we know that we have a

- not much competent US based hang glider manufacturer.

Hopefully you will do much better with France than I did the United States (and I think there are some good indications that you will).

I had not seen the importance...

I think you may have something of a point but...

This guy is - or, hopefully, was - CLUELESS. I don't want to beat up too much on a noncombatant because of lack of skill or feel for a glider but he doesn't bother...

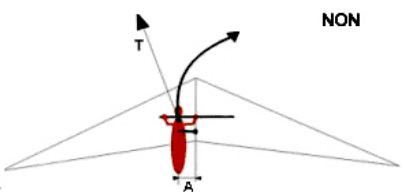

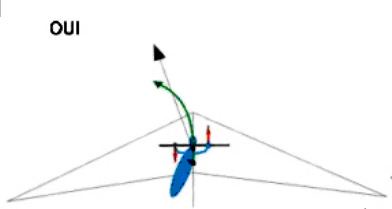

- centering his glider on the dolly.

- moving the left basetube bracket outboard

I can let him slide on some oscillation but he has all day on this tow to smooth things out and it never dawns on him to ease up on the input the tiniest bit. I almost blew lunch all over my keyboard on one of my viewings.

He makes hard corrections when there's nothing to correct.

- Sometimes he:

-- takes a nap when he REALLY needs to correct.

-- twists his body under the hang point when he needs to correct.

-- inputs for roll on the wrong side.

- When he needs to take way the fuck over three seconds ago he makes a pathetic little shift a couple of inches over - which is what finally locks the crap out of him with no help whatsoever from Mother Nature.

Trim point is the LEAST of this guy's problems. It was not safe to tow him even in smooth air.

And I don't see that he's holding anything significant in the way of bar pressure anyway.

Also...

- If you move the trim point a lot forward the glider still tows and maneuvers at the same airspeed - which is established by the tug's requirements. So the glider pilot is controlling the glider the same but with less effort.

- The glider pilot needs to be able to safely handle the glider at a reasonably wide range of airspeed because he will encounter a reasonably wide range range of airspeed.

- I don't like moving the trim point very far forward.

-- In my (somewhat limited) experience it's not a big deal to hold pressure with the trim point a good bit farther back than ideal - at least on tighter gliders.

-- In necessitates more crap in the airflow.

-- The farther forward the trim point the more and faster screwed you are if the bottom end of the bridle wraps.